Featured

The Pandemic Will Reduce Inequality—or Make It Worse

Bloomberg – The rich got even richer after the Great Recession, but the Great Depression changed the social order.

A recession is no picnic. A financial crisis leaves wounds that last for decades. A pandemic, though, can sow a unique kind of chaos.

The Black Death took a highly stratified medieval society and turned it upside down. With 75 million dead, Europe’s wealthy landowners couldn’t find enough people to tend their fields. When peasants—the essential workers of the day—demanded higher pay, the elites of the 14th century fought back with punitive laws, forced labor, and taxes. Even so, wages for the lowliest workers soared. In rural England, they doubled.

As epidemics go, the novel coronavirus is a relative lightweight—one that has nevertheless killed more than 200,000 people worldwide so far. Yet it’s accomplished something not seen in far deadlier outbreaks of the past: a simultaneous shutdown of much of the world’s commerce. No one can predict the long-term effects of a pandemic hitting an economy this complex and globalized.

For now, the most obvious guide to what comes next isn’t the Black Death, which precipitated the demise of European feudalism, but the Great Recession, which had more or less the opposite effect. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, inequality soared to heights not seen since the early part of the last century. At first, elites feared that much of their wealth would be wiped out in a globally synchronized market crash, à la 1929. But central banks pumped out trillions of dollars as monetary stimulus, markets recovered, and what followed may have been the best decade in history for the superwealthy.

Wall Street’s savviest investors are already pulling out their 2008 playbooks. The basic idea: Pay discount prices for ailing businesses and other distressed assets now, then cash in later when everything bounces back. In early April, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said it was considering setting up a $10 billion fund that would make loans to financially strapped companies. Executives at Apollo Global Management Inc. told investors during a March 24 call that the crisis was the private equity firm’s “time to shine.” And in an April 7 appearance on Bloomberg TV, billionaire Steve Schwarzman said his Blackstone Group Inc. was “looking aggressively” at making investments—even as he warned the pandemic could take a $5 trillion bite out of the $21 trillion U.S. economy.

Will the recovery from this crisis, whenever it arrives, be as unequal as the last one? There are reasons to think so. Even as business closings threaten to push U.S. unemployment past the 25% record set during the Great Depression, the stock market has bounced back from its March lows, buoyed by a multistage government rescue effort that is running in the trillions of dollars.

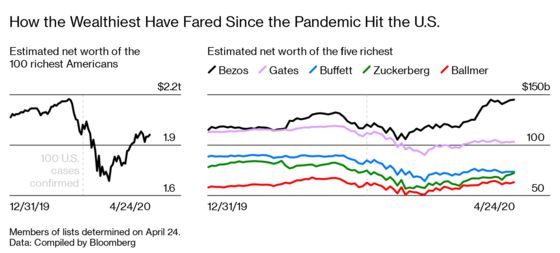

Some billionaires are faring better than others. The personal net worth of Amazon.com Inc. founder Jeff Bezos has increased more than $25 billion in just the two weeks from April 3 to April 17, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, while three heirs of Walmart Inc. founder Sam Walton are collectively more than $6 billion richer than they were at the start of the year.

So far, so 2008.

History is full of surprises, though, and no two crises are alike. Among the many ways 2020 could differ from 2008: This downturn may be worse. The International Monetary Fund predicts the world economy will shrink 3% this year, the most since the Great Depression. And the Great Depression had a very different impact on the world’s rich from the Great Recession.

“In 2008 they got away with it in a sense. They’re going to find that they can’t stop the pitchforks this time”

From 1929 to 1932, the top 0.1%’s share of all U.S. household wealth plunged by a third, and the top 0.01%’s portion fell by half—a funhouse-mirror opposite of their 2007-10 surge, according to estimates by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, a pair of professors at University of California at Berkeley who study economic inequality.

The 1929 Wall Street crash helped create a new economic order in the U.S. called welfare capitalism. With the New Deal, American workers gained a safety net. With World War II, they won leverage with employers and higher wages. The owners of the means of production—well, they didn’t do as well. By 1950 the very richest Americans, the top 0.01%, controlled just 2.3% of the nation’s wealth, less than a quarter of their share in 1929. Meanwhile, the bottom 90% of households had doubled their share.

One wild card, now and in past crises, is government policy. A dozen years after the financial crisis, it’s still galling to many that America’s leaders failed to prevent millions of foreclosures, even as bailout funds propped up the banks that originated mortgages that went toxic. “In 2008 they got away with it in a sense,” says University of Texas professor James Galbraith. “They’re going to find that they can’t stop the pitchforks this time.”

The Federal Reserve’s policies also contributed to widening the wealth divide. Record low interest rates—meant to stimulate borrowing and productive investment—pushed asset values ever higher. Corporate profits soared as the economy recovered much faster than workers’ wages. If you had capital to deploy in the bleak days of late 2008 and early 2009, you were lavishly rewarded. From the depths of the crisis to the beginning of this year, U.S. stocks more than quadrupled.

The rich have advantages in good times and bad. In an economic shock, “the issue of who has liquidity and who has access to credit lines becomes very important,” says Salvatore Morelli, an economist at City University of New York who has spent more than a decade studying how crises affect inequality. “The people who have liquidity jump in and buy those assets,” he says, then profit handily when the economy recovers.

After 2008, fortunes at the top ballooned even as the middle and working classes were hobbled by derailed careers, stagnant pay, and permanent losses on their biggest investments—their homes. From 2009 to 2012, when the economy was supposedly in recovery, the earnings of the bottom 50% of Americans fell 1.5%, while the top 1%’s income rose 21% and the top 0.1%’s earnings jumped 24%. By 2012 the top 0.1% of Americans were earning $6.7 million a year on average and collectively controlled a fifth of U.S. wealth, more than at any point since 1929.

Another increase in inequality may be inevitable. “Any recession, regardless of the cause, hits poor people disproportionately,” says Martin Eichenbaum, a professor of economics at Northwestern University.

Downturns also especially penalize those entering or exiting the job market. Millennials who graduated during the last recession paid a long-lasting penalty for their bad timing. In 2016 the average American under 35 was still earning less than the same age group in 2007, according to the Survey of Consumer Finance. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis found that the median household headed by someone born in the 1980s had 34% less wealth in 2016 than earlier generations held at the same age. Baby boomers approaching retirement will likewise struggle, especially if they lose their jobs and must tap savings early.

In normal times, being laid off can be devastating. Losing your job in a recession, when it’s harder to find another, often means you never recover. A U.S. study covering 1974 to 2008 found men laid off during periods of high unemployment lose out on the equivalent of 2.8 years of lifetime earnings, twice as much as men let go in better times.

What made the Great Recession great was that it waylaid people whether they lost their jobs or not. The main reason is that middle-class Americans have much of their wealth tied up in their homes, and their equity collapsed with the housing bubble. According to University of Bonn researchers in a forthcoming paper in the Journal of Political Economy, the bottom 90% of Americans consistently hold about half of U.S. housing wealth, but they have very little exposure to the markets—the top 10% own about 90% of stocks. When stocks rebound but real estate stagnates, the wealth gap widens.

More than 26 million Americans have filed for unemployment benefits in five weeks, a level of claims that implies a jobless rate of around 20%—twice the last recession’s peak of 10%. And some economists believe a 30% rate is possible. If these job losses sink the housing market again, the damage will be that much worse. Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody’s Analytics, estimates about 15 million American households with mortgages could stop paying if the economy stays closed through the summer or beyond.

Even if the economy snaps back quickly, the pandemic could create new inequality fault lines, such as a gap between those who have the luxury of working from home and those who cannot. Researchers at the University of Chicago have calculated that 37% of U.S. jobs “can plausibly be performed at home.”

-

Banking & Finance1 month ago

Banking & Finance1 month agoOman Oil Marketing Company Concludes Its Annual Health, Safety, Environment, and Quality Week, Reaffirming People and Safety as a Top Priority

-

News2 months ago

News2 months agoReport: How India & The Middle East Are Exploiting Immense Economic Synergies

-

Uncategorized2 months ago

Uncategorized2 months agoOman’s ISWK Cambridge Learners Achieve ‘Top in the World’ and National Honours in June 2025 Cambridge Series

-

News1 month ago

News1 month agoJamal Ahmed Al Harthy Honoured as ‘Pioneer in Youth Empowerment through Education and Sport’ at CSR Summit & Awards 2025

-

Economy2 months ago

Economy2 months agoPrime Minister of India Narendra Modi to Visit the Sultanate of Oman on 17-18 December

-

News2 months ago

News2 months agoIHE Launches Eicher Pro League of Trucks & Buses in Oman

-

Economy2 months ago

Economy2 months agoOman’s Net Wealth Reaches $300 Billion in 2024, Poised for Steady Growth

-

News2 months ago

News2 months agoLiva Insurance Honored with ‘Insurer of the Year’ Award for 2025